Much has been made over the years of the Nazi’s use of propaganda, both before and during the Second World War, to mould the attitudes and beliefs of German citizens. From films like Triumph of the Will and Olympia that glorified German achievements, and Jud Süß – perhaps the most anti-Semitic movie ever produced – to crude slogans daubed on walls, windows and doors across the Reich, propaganda was an ever-present feature of life in Nazi Germany. Yet, while almost all Nazi propaganda attempted to define a social narrative based on already accepted and understood social, political, racial or economic conventions, either past or dreamed of, for one artist, he could not have known just how insightful his piece of propaganda would prove when it was published in May 1939.

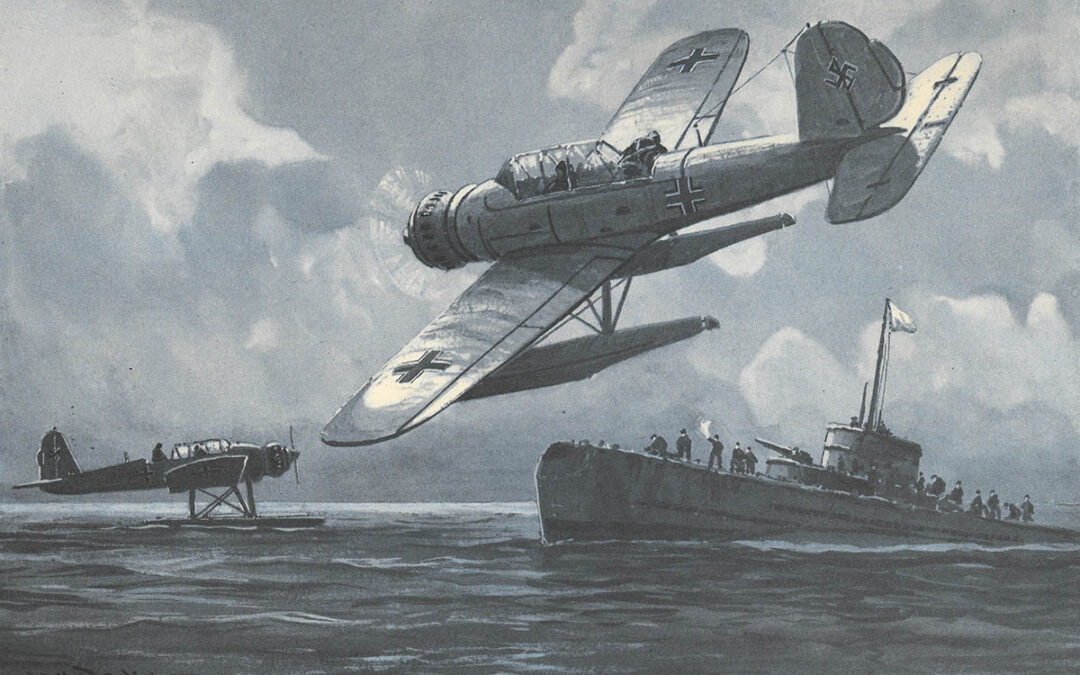

When art preempts reality: the May 1939 artwork that held so many key elements to the events of May 1940 and the demise of the British submarine, HMS Seal.

Air-mindedness had blossomed under the Nazis and from 1933 civilian interest in aviation, of all sorts, flourished. Capitalising on this, in the spring of 1939 Der Adler (The Eagle) was launched in conjunction with the Luftwaffe High Command. Its first issue went on sale on 1 March 1939 and was based solely on engaging with an audience besotted with flying. Unlike its British counterpart, Aeroplane, Der Adler was filled with articles interested in military flying. Most of the advertisements, too, were directed towards an image of the sophisticated airmen. Even the odd reference to gliding was phrased as a forerunner to military operations. There were pictures of strong young men with stern faces, servicemen with the giddy expression of relaxed joy, and beautiful women, all liberally strewn throughout the publication. And where the publishers could not fall back on photographic evidence for their tales of daring and romantic endeavours, there were the talented interpretations of an illustrator.

Published bi-weekly between March 1939 and September 1944, each Der Adler issue contained at least one illustration of a seemingly important event, either real or imagined. Most showed generic or purely fantastical situations, but for the illustrator of one image, what he foresaw as a sheer flight of fantasy turned out to be far more real – albeit in an abstract manner – than perhaps he had originally intended.

The 16 May 1939 edition of Der Adler ran an article titled ‘Fliegern Jagd U-Boote’, or ‘Fliers Hunt Submarines’. It was not the headline piece, or even the opening article. But accompanying the story was a series of illustrations depicting a solitary Heinkel 60 floatplane of a fictitious unit being launched from its parent ship and methodically searching out an enemy submarine threatening its fleet. Although the first four in the series were typical of German propaganda, the final illustration in the series of five showed the same He 60 bombing a surfaced submarine that sported the code ‘8L’ on its conning tower. The implication is clear, but what the artist of this particular illustration could never have foretold was just how eerily similar his illustration would prove, just twelve months later.

By May 1940, Britain had been at war with Germany for eight months. One of the former’s aims had been to confine German maritime trade with Scandinavia. As such, it had deployed several submarines to the area, some of which were charged with the more dangerous task of laying minefields along known shipping lanes. One such submarine was HMS Seal. Although the story of HMS Seal and her subsequent capture have been covered elsewhere, what remains pertinent is that she was captured eleven days short of the one-year anniversary of ‘Fliegern Jagd U-Boote’ being published. More interesting is that Seal was initially found and harassed by Arado 196 aircraft from Bordfliegergruppe 196, which had, until recently, been operating the He 60 – the same type depicted in the Der Adler illustration that accompanied the article. Meanwhile, the aircraft that finally affected the surrender of HMS Seal, a Heinkel 115 of 1./Küstenfliegergruppe 906, carried the unit code ‘8L’ – the very same sported by the fictitious boat in Fliegern Jagd U-Boote.

In German hands: the conning tower of HMS Seal, listing heavily under German protection ahead of its refit.

Of course the May 1939 Der Adler piece was pure fiction, although it undoubtedly harked back to the experiences of naval aviators during the First World War. Yet, unlike in the illustration, which suggested the ultimate destruction of the enemy submarine, in reality, the heavily damaged and listing HMS Seal was eventually towed to Frederikshavn, in Denmark, where it underwent preliminary repairs before being towed to Kiel for more extensive repairs. Once these were completed, Seal was pressed into service as the German submarine UB, under the command of Fregattenkapitän Bruno Mahn, who, at the age of 52, became the oldest active U-boat commander of the war. However, the high cost of refitting Seal and the lack of spares meant she remained nothing more than a propaganda piece throughout the war. Her only true value lay in the superior design of the British torpedo firing pistol, which was eventually copied and employed by the Germans in light of their own torpedo pistols’ inadequacies. With no operational value, UB was eventually decommissioned in July 1941 and finally scuttled in May 1945 in Heikendorf Bay at Kiel.

Obviously the Der Adler artist could never have known the striking similarities between his May 1939 illustration and the reality of May 1940 – for one thing, Küstenfliegergruppe 906 was not raised until October 1939! – however, working through all sorts of files, we at Air War Publications sometimes come across weird and wonderful anomalies like this, and just as with those that don’t make it to print, we feel they nonetheless need to be somehow recognised.